Back-to-back hurricanes left an unnerving scene on the Florida coast in November 2022: Several houses, and even swimming pools, were left dangling over the ocean as waves eroded the land beneath them. Dozens of homes and condo buildings in the Daytona Beach area were deemed unsafe.

The destruction has raised a disturbing question: How much property along the rest of the Florida coast is at risk of collapse, and can it be saved?

As the director of iAdapt, the International Center for Adaptation Planning and Design at the University of Florida, I have been studying climate adaptation issues for the last two decades to help answer these questions.

Rising seas, aging buildings

Living by the sea has a strong appeal in Florida – beautiful beaches, ocean views, and often pleasant breezes. However, there are also risks, and they are exacerbated by climate change.

Sea level is forecast to rise on average 10 to 14 inches (25-35 cm) on the U.S. East Coast over the next 30 years, and 14 to 18 inches (35-45 cm) on the Gulf Coast, as the planet warms. Rising temperatures are also increasing the intensity of hurricanes.

With higher seas and larger storm surges, ocean waves more easily erode beaches, weaken sea walls, and submerge cement foundations in corrosive salt water. Together with subsidence, or sinking land, they make coastal living riskier.

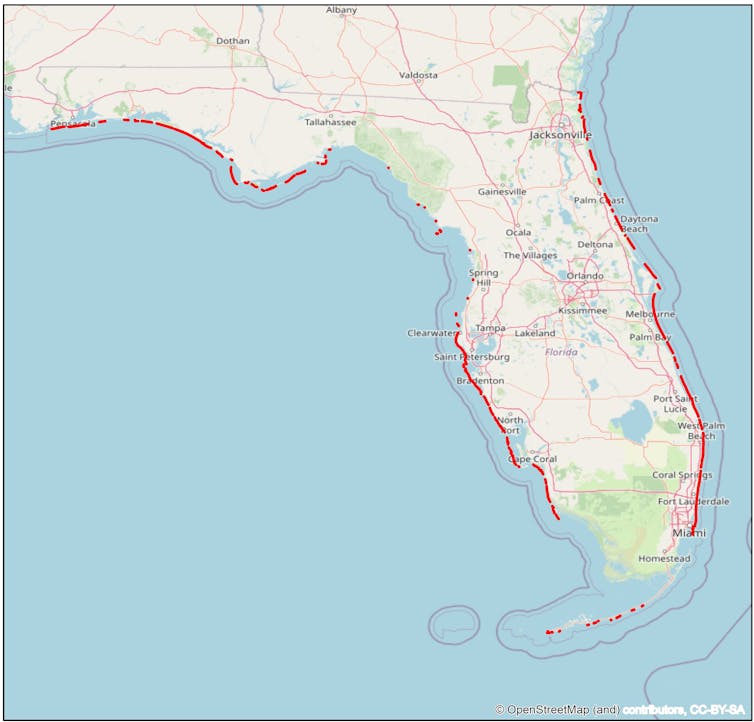

Florida Department of Environmental Protection, CC BY-SA

The risk of erosion varies depending on the soil, geology and natural shoreline changes. But it is widespread in U.S. coastal areas, particularly Florida. Maps produced by engineers at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection show most of Florida’s coast faces critical erosion risk.

Aging or poorly maintained buildings and sea walls, and older or poor construction methods and materials, can dramatically aggravate the risk.

Designing better building codes

So, what can be done to minimize the damage?

The first step is to build sturdier buildings and fortify existing ones according to advanced building codes.

Building codes change over time as risks rise and construction techniques and materials improve. For example, design criteria in the Florida Building Code for South Florida changed from requiring some new buildings to be able to withstand 146 mph sustained winds in 2002 to 195 mph winds in 2021, meaning a powerful Category 5 hurricane.

The town of Punta Gorda, near where Hurricane Ian made landfall in October 2022, showed how homes constructed to the latest building codes have a much better chance of survival.

Many of Punta Gorda’s buildings had been rebuilt after Hurricane Charley in 2004, shortly after the state updated the Florida Building Code. When Ian hit, they survived with less damage than those in neighboring towns. The updated code required new construction to be able to withstand hurricane-force winds, including having shutters or impact-resistant window glass.

Bryan R. Smith / AFP

However, even homes built to the latest codes can be vulnerable, because the codes don’t adequately address the environment that buildings sit on. A modern building in a low-lying coastal area could face damage in the future as sea level rises and the shoreline erodes, even if it meets the current flood zone elevation standards.

This is the problem coastal residents faced during Hurricanes Nicole and Ian. Flooding and erosion, exacerbated by sea-level rise, caused the most damage – not wind.

The dozens of beach houses and condo buildings that became unstable or collapsed in Volusia County during Hurricane Nicole might have seemed fine originally. But as the climate changes, the coastal environment changes, too, and one hurricane could render the building vulnerable. Hurricane Ian damaged sea walls in Volusia County, and some couldn’t be repaired before Nicole struck.

How to minimize the risk

The damage in the Daytona area in 2022 and the deadly collapse a year earlier of a condo tower in Surfside should be a wake-up call for all coastal communities.

Data and tools can show where coastal areas are most vulnerable. What is lacking are policies and enforcement.

Florida recently began requiring that state-financed constructors conduct a sea-level impact study before starting construction of a coastal structure. I believe it’s time to apply this new rule to any new construction, regardless of the funding source.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

A comprehensive sea-level impact study requirement should also allow for risk-based enforcement, including barring construction in high-risk areas.

Similarly, vulnerability audits – particularly for multistory buildings built before 2002 – can check the integrity of an existing structure and help spot new environmental risks from sea-level rise and beach erosion. Before 2002, the building standard was low and enforcement was lacking, so many of the materials and the structures used in those buildings aren’t up to the standards of today.

What property owners can do

There is a range of techniques homeowners can use to fortify homes from flood risks.

In some places, that may mean elevating the house or improving the lot grading so surface water runs away from the building. Installing a sump pump and remodeling with storm-resistant building materials can help.

FEMA suggests other measures to protect against coastal erosion, such as replenishing beach sand, strengthening sea walls and anchoring the home. Engineering can help communities, temporarily at least, through sea walls, ponds and increased drainage. But in the long term, communities will have to assess the vulnerability of coastal areas. Sometimes the answer is to relocate.

However, there’s a disturbing trend after hurricanes, and we’re seeing it with Ian: Many damaged areas see lots of money pouring in to rebuild in the same vulnerable locations. An important question communities should be asking is, if these are already in high-risk areas, why rebuild in the same place?

![]()

Zhong-Ren Peng receives funding from National Science Foundation, Florida Sea Grant, and Florida Department of Transportation.

This content was originally published here.