Amid the scale and sweep of the list of decisions made by the Whitlam government in their first week in office, most people remember the big changes: freeing all draft resisters from prison, or official recognition of Communist China.

The removal of the sales tax on the contraceptive pill, and adding it to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, which came into effect on December 9 1972, is easily overlooked. Yet this reform was both symbolic and materially important. It signalled to Australian women that their new government would be much more responsive to their demands for reproductive rights and freedoms, and ushered in a wave of feminist reforms under the Whitlam government.

The popularity of the pill

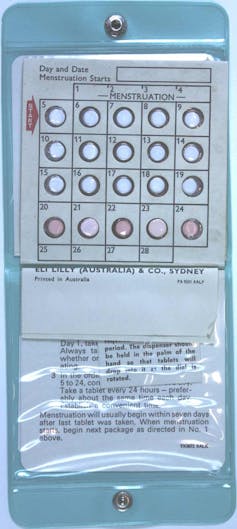

The introduction of the contraceptive pill in January 1961 had brought the topic of contraception into the open in Australia. It was hailed as a reliable and convenient way for married couples to plan their families.

The pill also made an important contribution to the changing sexual climate of the late 1960s. By removing the fear of pregnancy, the pill helped to change women’s attitude towards sex. Concerns about side-effects, cost and availability deterred some women from taking it, but by the early 1970s, one in every four Australian women had a prescription.

However, many doctors refused to prescribe the pill to single women, and it remained out of reach to many working class women due to its cost. At the time, Australia had banned the advertising of contraceptives, and the sales taxes and tariffs applied to contraceptives added to their expense. As the Women’s Electoral Lobby liked to point out, the 27% sales tax on the pill was the same as that applied to mink coats.

Growing calls for reproductive rights

National Museum of Australia

Given many women’s difficulties obtaining the pill, it is unsurprising that access to abortion became a significant political issue in the 1960s. The Abortion Law Reform Association (ALRA) was formed in 1967, and by 1971 it had branches across Australia.

The laws criminalising abortion were state-based, and these laws were liberalised in Victoria in 1969 and NSW in 1971. This liberalisation did not grant women the “right” to abortion, but clarified the conditions under which a doctor could perform an abortion lawfully.

Under the liberalised law, a doctor could perform an abortion legally when they believed that it was “necessary to preserve a woman from serious danger to her life or to her physical or mental health”.

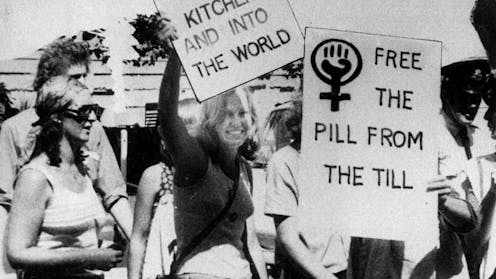

These reforms were focused on doctors’ rights, rather than women’s. But at the same time, the women’s liberation movement was demanding bodily autonomy and reproductive freedom for women. They wanted abortion on request, free birth control, and free childcare, arguing that women could only fully participate in society as equal citizens if they had control over their fertility. Contraception was a fundamental feminist issue.

Whitlam, WEL and reproductive rights

As part of his reshaping of the Labor party to make it electable and modern, Whitlam extended the ALP’s language of equal opportunity beyond class to encompass migrants, women and Indigenous Australians.

While Labor’s 1972 election platform only addressed women’s specific needs in relation to childcare, Whitlam was a vocal supporter of women’s access to affordable contraception and abortion, as was his wife, Margaret.

Yet it was the Women’s Electoral Lobby that was perhaps most crucial in reshaping Labor policy on women’s issues. Formed in March 1972 by abortion law reform campaigner Beatrice Faust, WEL wanted to place women’s concerns on the political agenda by surveying all candidates in the 1972 election on issues women believed were important. One-third of those questions were on contraception and sex education.

Apart from the candidate survey, which generated huge publicity in the lead up to the 1972 election, WEL also engaged in lobbying, and made a submission to a 1972 tariff inquiry calling for a reduction in tariffs on contraceptives. As Marian Sawer notes in her history of WEL, this put family planning issues on the ALP’s agenda. Within a week of WEL’s submission, the shadow health minister, Bill Hayden, said a Labor government would remove the sales tax on contraceptives and support the development of a network of family planning clinics.

This early action made the contraceptive pill cheaper; the Whitlam government’s subsequent actions made contraception more widely available. The government made numerous grants to family planning organisations, and between 1973 and 1974, around 100 family planning clinics opened throughout Australia.

These clinics were important for several reasons: they took away some of the stigma of having to approach your doctor for a prescription for the pill, especially for young single women, and the location of clinics in working class areas helped increase uptake of the pill among working class women.

This early decision on the pill was the first of the Whitlam government’s reforms on reproductive rights. The government made an unsuccessful attempt to reform the law on abortion in the ACT. However, while it failed to change the law, it did create the Royal Commission on Human Relationships, a far-reaching inquiry into sexuality, gender and family life. In the words of Elizabeth Reid, the Whitlam government’s advisor to women’s affairs (the first position of that kind in the world), the commission helped foster a “revolutionary consciousness” that she saw as vital to driving structural and cultural change.

It inquired into why women had abortions and planned their families, recommending new laws and practices to respond to changing times. The government also funded women’s refuges and women’s health centres, which helped share new knowledge about contraception. It expanded the provision of childcare, and, through Reid, started the long, slow process of making Australian governments more responsive to women’s needs. It is an ongoing journey.

In his book The Whitlam Government, Whitlam remarked that

the many and diverse achievements of the Government did much to correct an alarming history within the Labor Party of ignorance and inactivity on women’s issues.

His government recognised women as independent political subjects with roles to play beyond motherhood. It also recognised the central principle of second wave feminism: namely, that women needed bodily autonomy and control over their fertility before they could participate in society on their own terms.

Read more:

Damned Whores and God’s Police is still relevant to Australia 40 years on – more’s the pity

The decision was also an important signal to the women’s movement: an assurance that they took women’s concerns seriously, and that the rights of women were important to the Labor party as they built an expanded coalition of voters.

The removal of sales tax on the pill was fitting recognition of women’s new political engagement, and the beginning of a productive relationship between the government and the women’s movement.

On the 50th anniversary of this symbolic and important decision, it’s worth remembering what governments and activists can achieve when they work together to improve the lives of Australian women.

![]()

Michelle Arrow receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She has worked as a campaign volunteer for the Australian Labor Party.

This content was originally published here.