The tale of J. Robert Oppenheimer ranks among the most haunting and consequential of the modern era, yet all but its barest outlines are largely forgotten. This makes Christopher Nolan’s eponymous film both vital and challenging: It’s a complicated story, as world-altering sagas tend to be, so who knows whether—even aside from its three-hour length—many moviegoers will stick with it.

You should. It’s a mind-blower, not just for Nolan’s artistic innovations, but also because the story itself is disturbing, tragic, even shocking, and the fact that most of its details will be new to most viewers might make them probe it more deeply. Some are already probing. The magisterial Oppenheimer biography on which the film is based, Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s American Prometheus, published in 2005, recently hit the list of paperback bestsellers for the first time ever.

As someone who has read a lot (and written two books) about nuclear history, I can say that, for the most part and as far as it goes (important qualifiers, which I’ll soon get to), the film is a faithful portrait of what really happened—especially, perhaps, in the scenes that some might assume are made-up or exaggerated.

Oppenheimer was 38 when he was appointed director of the Manhattan Project, the $2 billion, top-secret World War II program to build the atomic bomb.* Though a brilliant theoretical physicist and a pioneer in the newfangled field of quantum mechanics, he had never managed any project, was inept at experimental (i.e., practical, bricks-and-mortar) physics, and wasn’t even the most talented scientist of any sort among the hundreds who worked around him. But he was enormously charismatic, grasped concepts with preternatural speed, and saw how progress in one department could jolt progress in another department, so he made it work in ways that possibly no one else could have.

After the war, he became the most famous scientist in the world, appearing on the cover of Time magazine and hailed as “the father of the atomic bomb.” A few years later, he raised doubts about his work, opposed production of the much more powerful hydrogen bomb, called for international controls on all weapons of mass destruction, and as a result, got blackballed by key figures in the nuclear establishment—his security clearance revoked by a tribunal as rigged and vindictive as any of the Cold War’s various other Red-baiting panels.

Yet as absurd as it was to tarnish Oppenheimer as a Soviet spy, it is equally mistaken to sanctify him—as many of his defenders have done—as a peace-loving martyr. The film avoids that trap, painting a complex portrait: a tortured soul, enthralled by the science, then racked by guilt over the hellscape it unleashed. He’s insistent on his independence as a scientist, but also pliant in his role as mere adviser to authority. He’s certain of his convictions, but ambivalent about almost everything.

Witnessing the A-bomb’s first test in the desert far outside Los Alamos, the New Mexico town where much of the bomb-building took place, he really did (as the film depicts) recite the line from the Bhagavad-Gita, “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” At his meeting with President Harry Truman, after the bombs he helped build incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he really did say “I have blood on my hands.” And Truman, who lost no sleep over his decision to drop the bombs, really said to an aide afterward (though not within earshot of Oppenheimer, as he does in the film), “Don’t let that crybaby in here again.”

Yet Oppenheimer was also gung-ho about the bomb, waving his fist at a rally of the scientists after they heard the news of Hiroshima, bellowing—to applause and laughter—that he was sure the Japanese didn’t like it, and expressing regret only that he and his colleagues hadn’t built the bomb in time to use it on the Germans.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt instigated the Manhattan Project in 1942, after Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, two of the most prominent physicists of the day, wrote him a letter warning that German scientists had figured out how to split an atom, that they could turn this discovery into a very powerful bomb, and that we needed to beat them to it or risk losing the war. As it happened, the Allied armies defeated the Nazis in the spring of 1945, before the German scientists succeeded. But Japan fought on, so Truman—who became president after FDR died—shifted the plans to drop the bomb on Japan.

Some of the Manhattan Project’s scientists—including Szilard—petitioned Truman to drop the bomb on an unpopulated island as a demonstration of its power, giving the Japanese a chance to surrender before it was unleashed on their cities. Oppenheimer urged his colleagues not to sign Szilard’s letter, saying such matters should be left to political leaders and endorsing the official view that if we didn’t drop the bomb, thousands of American soldiers would die in an invasion of the Japanese mainland. (The debate over this question is still unsettled.) The film is clear on all of this. It points out, as well, that Oppenheimer served on the official commission that selected the bomb’s targets.

Oppenheimer fell into a funk after the war, perhaps as a result of viewing footage of the atrocities that his bombs inflicted on tens of thousands of civilians. But many military officers and some scientists, foreseeing a possible war with Russia, pushed to build a hydrogen bomb, which would be 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bombs that ended World War II. Oppenheimer opposed the H-bomb project, but not entirely for moral reasons. At first, he thought it was infeasible. Then, when the math proved it feasible, he dropped his resistance, admitting that it was too “technically sweet” not to develop. (The film does not quote this rather famous line of his.) Still, he remained unenthusiastic, worrying that the H-bomb would divert money from Hiroshima-type A-bombs, which he thought the Army should continue building as weapons to be used on the battlefield if the Soviets invaded Western Europe. He argued that H-bombs were too powerful for battlefield targets—they could destroy only big cities—and, if the Russians built them, as they would if we did, a war would devastate American cities, too. He did eventually come to the view, as portrayed in the film, that this mutual vulnerability might deter both sides from using the weapons or even from going to war at all. But he was not opposed to nuclear weapons in general.

At this point, in the early 1950s, Oppenheimer was still very influential—among fellow scientists, legislators, and the public. He was chairman of the advisory council to the Atomic Energy Commission and president of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, which had previously been led by Einstein. His hedged attitude toward the H-bomb threatened the project’s funding. And so its leading advocates set out to destroy him.

They created a tribunal to investigate whether his security clearance should be revoked. (Without a Q security clearance, he could play no role in setting, or even learning about, atomic policy.) Oppenheimer left himself open to attack. In the 1930s and early ’40s, he had been a “fellow traveler”—probably not a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, but an active supporter of some of its causes, which in the day included racial integration, a minimum wage, and aiding the anti-fascist soldiers in the Spanish Civil War. Not only that, his wife, Kitty (played by Emily Blunt), had once been a party member, as had his brother and several of his close friends, and he attended several meetings of the party’s chapter in Berkeley, where he was teaching physics. Even after he was appointed director of the Manhattan Project in 1943, his security clearance was held up because of these connections.* The project’s military director, Gen. Leslie Groves (played by Matt Damon), had to force the clearance through.

It was one thing to hold left-wing ideas in the ’30s, during the Depression, or even in the early ’40s, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union were allies in the war against Nazi Germany. But by 1954, when the tribunal held its hearings, we were in the thick of the Cold War. Distinctions between a fellow traveler, a Communist, and a Soviet spy were waved away as trivial.

The FBI had been tapping Oppenheimer’s phone for years. The tribunal obtained transcripts of the taps, and because the hearings weren’t a trial, they didn’t feel the need to share the material with Oppenheimer or his lawyers. They even had phone taps of his calls with his lawyers. They also deliberately humiliated Oppenheimer, catching him on discrepancies between his memory and the record of the phone taps, and at one point—while his wife was in the hearing room—asked about an affair he’d had with a former girlfriend, Jean Tatlock, played in the movie by Florence Pugh. (Kitty knew about it, but was mortified that her husband’s tormentors did too.)

Much of the film is devoted to these hearings. His interrogators are portrayed as so brazenly hostile, you may wonder if the scenes are accurate—and they are. They’re taken, almost verbatim, from the hearing’s transcripts, which were published many years ago.

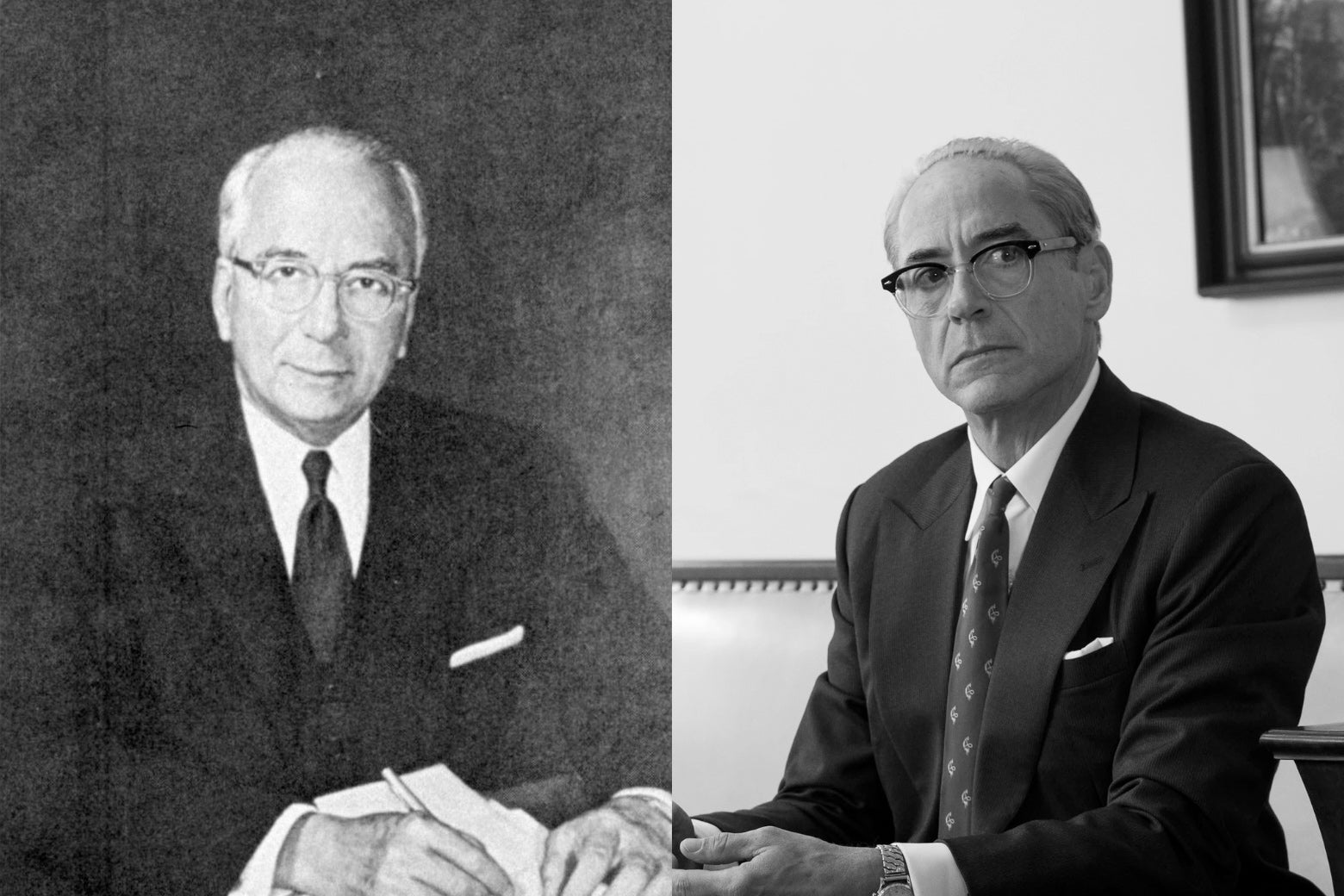

Nolan is also accurate in depicting the tribunal as an instrument of personal revenge—the creation of Lewis Strauss, a shrewd, self-made financier and chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. Not only was Strauss (cannily played by Robert Downey Jr.) an ardent advocate of the H-bomb, he had also been humiliated by Oppenheimer, first at a public congressional hearing, then repeatedly at AEC meetings—and Strauss never forgot this.

Oppenheimer’s tendency to badger or ridicule those who weren’t as smart as he was (which included almost everyone) earned him several enemies. And he made a mistake in alienating Strauss, whose capacity for holding grudges was limitless. (One of Strauss’ colleagues later said, “If you disagree with Lewis about anything, he assumes you’re just a fool at first. But if you go on disagreeing with him, he concludes you must be a traitor.”)

Further damage was done by Edward Teller (played by Benny Safdie), one of the Los Alamos scientists. Teller had been bored by the A-bomb project, even while it was going on, and wanted to move ahead with an H-bomb. He and Oppenheimer quarreled about this. After the war, Teller pushed to create a separate lab dedicated to building H-bombs. Oppenheimer opposed the idea, so Teller defanged him by testifying against him at the hearing.

The tribunal voted 2–1 to revoke Oppenheimer’s clearance. Teller got his money for a new lab in Livermore, California. (Both Los Alamos and Livermore are still in operation.) The episode unleashed a scandal and created schisms within the scientific community—the Teller hawks vs. the Oppenheimer doves, a divide that pushed both sets of partisans to harden their positions. It also drove a rift between scientists and the government. Many scientists doubted they could offer advice without compromising their principles. The loss to the public was incalculable.

Oppenheimer was eventually vindicated, in two stages. In 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower nominated Strauss to be secretary of commerce. But one of the Manhattan Project’s scientists, David Hill (rivetingly played by Rami Malek), testified that Strauss had organized the campaign against Oppenheimer as an act of petty vengeance. As a result, the Senate voted down the nomination, the first time a Cabinet nominee had been rejected since 1925. (This scene is drawn from the Senate hearing’s transcript, which, by the way, was not in Bird and Sherwin’s biography. Nolan dug it up on his own.)

Then, in December 1963, President Lyndon Johnson awarded Oppenheimer the Fermi Award, one of the most prestigious in American science, carrying a cash award of $50,000 (the equivalent of almost $500,000 today). Teller, who was at the White House ceremony, offered his hand to Oppenheimer, who shook it. Kitty did not; she scowled, properly. The film accurately depicts both moments of triumph. (Their marriage was even more tempestuous than the film depicts, though it’s accurate in showing her as repeatedly—and wisely—urging her husband to fight back against his foes.)

Even clocking in at three hours, there are several aspects of this story that go untouched. Don’t expect a group portrait of scientists in collaboration. The Manhattan Project was a vast team effort, but the film won’t show you much of that. Except for Teller, and to some extent Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett) and Isidor Rabi (David Krumholtz), all the other scientists—such brilliant, colorful figures as Hans Bethe, Enrico Fermi, George Kistiakowsky, and many others—are presented as ciphers in walk-on cameos. For a fuller view of the project, watch (if you can find it) the BBC’s 1980 seven-part drama, also called Oppenheimer, with Sam Waterston in the starring role. Or, better yet, read American Prometheus or Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

Christopher Nolan Is for the Girlies

Nor will this film teach you much about fission, fusion, or quantum physics, though that may be asking too much of any movie. Nolan creates split-second images of starbursts, black holes, and galaxy-like explosions, and they have a dramatic effect. His re-creation of the first atom-bomb test is awesomely immersive.

The entire film is an experiment in immersion, an attempt to make us feel what it’s like to be Robert Oppenheimer, and it succeeds to a remarkable degree. Cillian Murphy, in the title role, helps: His lanky frame, awkward gait, and wide eyes convey the impression of an ethereal being, a creature from another dimension, which Oppenheimer sometimes seemed to be. He not only grasped the most arcane new concepts in physics, but also read deeply in history, philosophy, and literature, in several languages, which he mastered with absurd alacrity. (The film is accurate in showing him give a lecture on quantum mechanics to an audience in the Netherlands in Dutch, based on having studied the language for six weeks ahead of time.) We do get a sense of Oppenheimer’s magnetism, his arrogance, and his touch of craziness—and it may be that a man had to have all three to absorb so fully and instinctively the crazy-quilt eeriness of quantum physics. (It is also true, by the way, that as a grad student, he left a poison apple for one of his teachers.)

The film ends with a flashback to soon after the war, Oppenheimer talking with Einstein (charmingly played by Tom Conti) by a lake in Princeton, the two of them wondering whether their joint invention might someday engulf the world in flames. This scene never happened, or at least it’s not in Bird and Sherwin’s biography. But it’s an effective bit of dramatic license, capturing the guilt felt by many of the scientists who worked on the bomb. Some, led by Szilard and to some extent joined by Oppenheimer, became ardent activists for nuclear arms control.

Nolan means for Oppenheimer to be more than a mere biopic or historical drama. At a panel after a screening of the film on Saturday, he said that scientists today are facing their own “Oppenheimer moment,” especially in the development of artificial intelligence, another new technology that seems too technically sweet to resist but may wind up reshaping humanity more than humanity can shape it.

But he also reminded the audience that the hydrogen bomb is still with us, and that just because it has helped deter a war between the major powers for the 78 years since Hiroshima, our luck might not last forever. We are all still living in Oppenheimer’s era.

Correction, July 19, 2023: This article originally described Oppenheimer as the director of the Manhattan Project. He was the director of the Manhattan Project’s central laboratory in Los Alamos.

This content was originally published here.